“A Buffalo Neighborhood Renews Its Olmsted Legacy (2012)”

Below article appeared in Library of American Landscape History.

“A Buffalo Neighborhood Renews Its Olmsted Legacy (2012)

Humboldt Park, Buffalo, New York

When Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux began work on the nation’s first comprehensive municipal park system in 1869, Buffalo was the eighth largest city in the country and one of the busiest ports on earth. Functioning as the gateway to the Midwest via the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes, the city offered the partners an opportunity to improve an existing grid with a green network of parks and sinuous parkways. Late in life, Olmsted declared Buffalo to be “the best planned city, as to its streets, public places, and grounds, in the United States, if not the world.””

“The appeal of a lushly planted public landscape attracted upscale development, and soon the works of leading architects from New York City and Chicago were enlivening the city’s streets. Into the mid-twentieth century, the parks’ mature plantings provided Buffalo’s neighborhoods with high-canopied shade, lakes and picnic groves, and miles of walking paths. Two-hundred-foot-wide median strips in the parkways even boasted equestrian trails in a woodland setting, while cars whooshed past on either side.

Olmsted and Vaux, however, did not foresee the trends that cast Buffalo among the financially distressed cities of the “rust belt” in the late twentieth century. Like parks in other large northeastern cities, Buffalo’s were neglected and, in some cases, destroyed. The Olmsted legacy faded from popular memory. “When I first moved to Buffalo five years ago, most citizens here didn’t even recognize the Olmsted name. That has changed dramatically,” says Thomas Herrera-Mishler, president and chief executive officer of Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy. Now the regional convention and visitors bureau, Visit Buffalo Niagara, touts the Olmsted parks among Buffalo’s attractions. “This is the green infrastructure that gives us a competitive edge,” Herrera-Mishler says. The 2011 National Trust for Historic Preservation conference, hosted in Buffalo in October of last year, brought the Olmsted legacy to national attention, featuring park tours by members of the National Association for Olmsted Parks, the Trust for Public Land, and other nationally prominent historic preservation advocates.

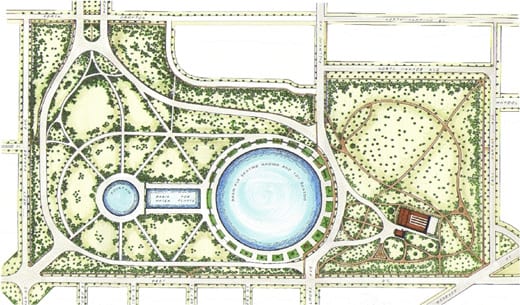

Equally important, the conference helped raise local awareness of the park system’s cachet. “The conference brought the valued perspective of experts who recognize these treasures, giving residents a greater appreciation for them,” says Otis Glover, strategic planner and external affairs officer at the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy. “All of our cultural treasures are in the footprint of the Olmsted landscape.” In particular, the attention boosted long-standing efforts by residents to revitalize a predominantly African American neighborhood surrounding one of the city’s principal Olmsted parks, on Buffalo’s east side. Olmsted designed the park, originally known as the Parade, as a military parade ground. It was used for this purpose only once, and in 1896, John Charles Olmsted redesigned it for general recreation, adding three axial water features, including a vast circular pool for wading, toy boating, and skating. Humboldt Basin, at five hundred feet in diameter and five acres in area, remains the country’s largest wading pool. Its grandeur was echoed in other amenities—including greenhouses and a casino building—throughout the park. After its redesign, the park was renamed Humboldt Park, after Humboldt Parkway, itself named after the great explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. Like the system’s other parkways, this was a broad median of wooded trails and grassy meadows, which created a pedestrian and vehicular link to Delaware Park, the system’s anchor.

Various encroachments gobbled up space in Humboldt Park during the twentieth century. The crowning blow, however, came in the 1960s with the construction of Kensington Expressway, a multilane highway that lopped off the park’s northwest corner and erased the parkway, splitting the neighborhood and severing it from the rest of the city. “For four decades the community has been devastated by disenfranchisement and division,” Glover says. For him and others, the multigenerational impact of the highway underscores the profound significance of access to open space and citywide connections. The sunken six-lane expressway, locally dubbed “the canyon,” whisks suburban commuters to downtown offices, stranding local businesses and creating an aesthetic blight that has contributed to sinking property values. Humboldt Park was renamed to honor Martin Luther King Jr. in 1977, but it continued to decay. The water features, including the basin, stood empty. A plan to take parkland and build a magnet school next to the Buffalo Museum of Science, which had already been built in the park, galvanized the Buffalo Friends of the Olmsted Parks, sparking a battle that ended in the state supreme court. The battle was lost, but the organization that eventually grew into the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy was born.

In the mid-1990s, the community and the conservancy started actively campaigning to revitalize the neighborhood and its park, led by the Martin Luther King Jr. Coalition. When the city announced plans to convert the abandoned Humboldt Basin into a fishing pond, the neighborhood mounted a protest and demanded the return of the wading pool. Richard Cummings, a businessman who lives on the park, is a trustee of both the coalition and the parks conservancy. “We want to reclaim the community as it was in the early 1960s, before the destruction of the Humboldt Parkway,” he says. Cummings attests that the green landscape of the former park and parkway—and the loss of it—exerts a tangible influence: “It affects pride and real-estate value and the way people approach our community.”

During the same period, the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy had taken over maintenance of the Buffalo Olmsted parks and embarked on a comprehensive master planning process, soliciting the community’s views about how to rehabilitate Martin Luther King Jr. Park. Together they selected a number of major projects, including the wading pool. Bringing back the pool proved complicated, however; modern health and safety codes required fencing, a massive water-purification system, and sixty-five lifeguards for a pool less than three feet deep. “So we focused on how to make water available in some form for seasonal recreation,” says landscape architect Mark V. Mistretta, RLA, ASLA, of Wendel Companies, a Buffalo native and a founding member of the parks conservancy. “We decided to create a large splash pad, providing big spray events in summer. In spring and fall it will be a reflective basin. When it freezes, we will have a great skating rink.” With $4.2 million in funding from the City of Buffalo, the State of New York, and BlueCross BlueShield of Western New York, the pool will open this summer.

In a parallel effort, the Reclaiming Our Community Coalition, which includes the parks conservancy as well as businesses and institutions, such as the Buffalo Museum of Science, that are located in and around the park, is advocating for the city to cap more than a mile of the Kensington Expressway and replicate the former parkway landscape on the covered portion, says Cummings, who also serves on this coalition’s board. The state has provided $2 million to fund preliminary studies for the proposed project, which would cost an estimated $465 million, according to a recent Buffalo newspaper report. LALH vice president Ethan Carr, FASLA, a trustee of the National Association for Olmsted Parks, has been speaking with coalition members. Carr agrees that “restoring the parkway is about restoring the neighborhood.” He adds, “Olmsted’s vision was never about just providing trees and grass. It wasn’t just about building parks and parkways. It was about building communities, creating vital neighborhoods that were centered around the parks. That’s why they were built.”

—Jane Roy Brown”

To download a .pdf of this article, click here.