In the News

With a Year Left, U.S. Transportation Secretary Sets New Goals

Posted: January 26, 2016

Source: Governing

U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx, a former mayor of Charlotte, N.C., has plenty left to do in the Obama administration’s final year. His agency is pushing cities to improve bicycle and pedestrian safety, hosting a “Smart City” competition to showcase how technology can improve transportation, and doling out money from a new five-year, $305 billion federal transportation package.

But in recent weeks, Foxx added two more items that resonate with him personally to his packed agenda. First, he wants to tear down — or at least improve — transportation infrastructure that isolates communities. Second, he wants to find a way for cities to get federal transportation money directly, rather than have it flow almost exclusively through states.

If successful, Foxx would reverse decades of policy. Doing that by next January seems implausible, but he can at least plant the seeds for long-term change.

Every community, he told mayors and transportation experts at the annual Transportation Research Board conference earlier this month, has examples of infrastructure that divided communities when they were built.

“We built highways and railways and airports that literally carved up communities, leaving bulldozed homes, broken dreams and in fact sapping many families of the one asset they had: their home,” he said.

Foxx experienced the problem firsthand growing up in his grandparents’ house in Charlotte. He saw a fence two blocks away from his backyard for Interstate 85, and when he walked out of their house and turned right, he saw Interstate 77.

“Had I been born 10 years before, where those fences were would have been through streets with houses and people. My neighborhood had one way in and one way out, and that was a choice,” said Foxx.

While he moved on from that neighborhood, that sort of infrastructure dividing line trapped many people like him. Having neighborhoods so isolated, said the secretary, not only discourages good housing, grocery stores, pharmacies and other services from coming into those areas, it also makes it harder for residents to get to their jobs. Foxx pointed to the story of James Robertson, a Detroit resident who walked 21 miles a day to get to work and back because the area’s public transportation is so poor. Foxx last year directed more than $25 million in federal funding to help the Motor City improve its transit.

Several U.S. cities — with the help of the U.S. Department of Transportation — have already either torn down above-ground stretches of highways or are studying that possibility. The idea has gained appeal as local governments and transportation planners promote “complete streets” that accommodate a variety of uses and are particularly friendly for cyclists and pedestrians — not just cars. One of the most widely cited examples is San Francisco’s decision to tear down its Embarcadero Freeway that was damaged in the 1989 earthquake. The removal of the highway reconnected the city to its waterfront and spurred development.

But getting rid of existing highways is rarely easy. Building a tunnel can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, while converting existing freeways into slower-moving boulevards can increase traffic and congestion.

Foxx’s final-year concerns aren’t just about infrastructure that isolates communities.

When talking to the U.S. Conference of Mayors earlier this month, he added another task based on his personal experience: dedicating more federal transportation money for cities instead of states.

“I was a mayor too,” he said, referring to his tenure as the head of North Carolina’s biggest city. “I saw a lot of money come into our state … and I watched it go around like a pinball. By the time it got back to me, it was a very small fraction of what it had been.”

Foxx called for an overhaul of the way the federal government doles out transportation money. He said the current system, which distributes money primarily through states, “prevents local governments from being able to effectively address some of the most important issues facing their communities.”

He also argued that money should be distributed based on current demand for services, not by predetermined formulas. The federal government spends 80 percent of its money on roads and highways, yet demand is shifting — especially among younger Americans — to car-sharing, transit, bicycling and walking.

Cities have long complained about how they get federal funding yet have made little headway. The five-year transportation funding package that Congress passed last year made small changes to give metropolitan areas more say in how the money is spent, but 93 percent of federal transportation money will still flow through the states. Foxx said his department would work over the next year to come up with an alternative way of deciding how that money should be distributed and spent.

But transportation advocates doubt change will come soon.

Jim Tymon, the director of policy and management at the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, said any changes aren’t likely to occur until the current five-year transportation package expires. He also downplayed the tension between state transportation departments and local governments. “There are unmet transportation needs at all levels of governments,” said Tymon. “State DOTs would say the same thing; they would love more federal transportation money.”

Money, however, is hard to come by in the transportation world. Congress didn’t include much new money in its recent funding package, and with the federal gas tax stuck at the same per-gallon rate since 1993, the revenue it generates for roads and other transportation needs has lost its buying power over the years.

Freeways without Futures 2019

Routes 33 and 198 have made the 2019 list for the Congress for the New Urbanism’s Freeways without Futures!

As the name suggests, cities across America are working to remove the imprint of aging expressways from parks and neighborhoods that have long suffered from disinvestments.

Local Coverage:

WKBW

https://www.wkbw.com/news/local-news/go-bike-buffalo-unveils-2019-slow-roll-schedule

WGRZ

Buffalo Rising

Buffalo News

WBEN

https://wben.radio.com/articles/report-recommends-redesigning-kensington-and-scajaquada-expressways

Other cities that made this year’s list include:

- I-10 (Claiborne Expressway), New Orleans, Louisiana

- I-275, Tampa, Florida

- I-35, Austin, Texas

- I-345, Dallas, Texas

- I-5, Portland, Oregon

- I-64, Louisville, Kentucky

- I-70, Denver, Colorado

- I-81, Syracuse, New York

- I-980, Oakland, California

Full Report:

https://www.cnu.org/sites/default/files/FreewaysWithoutFutures_2019.pdf

“Bury This Big Mistake”

Below is an article featured in Artvoice March 3, 2010. Images used in the article were provided to Artvoice by David Torke.

“Bury This Big Mistake

Transportation officials begin studying several expensive ways — and one intriguing bargain — to reclaim Humboldt Parkway.

Sixty-two years ago, William Gallancy, an associate engineer with New York State’s Department of Public Works, told a standing-room-only crowd at St. James Evangelical and Reformed Church on High Street that the Kensington Expressway was the best solution to East Buffalo’s problems. Traffic congestion on the neighborhood’s thoroughfares was bad and getting worse, he explained. “Gallancy said 70,000 vehicles a day cram that section’s main arteries—Main, Kensington, Genesee, Bailey and Walden,” according to a Buffalo News account of the meeting. “And, he added, the growth of suburbs and congestion of traffic continues to increase at a tremendous rate.

“Unless something is done to relieve this congestion, he said, property values will drop alarmingly. ‘It is doing more to depress property values than anything else,’ he warned. ‘We must save the city from becoming a backyard for its suburbs.’”

Well. That certainly didn’t work.

The $45 million Kensington Expressway tore up Frederick Law Olmsted’s tree-lined Humboldt Parkway, claimed hundreds of homes in previously stable neighborhoods, ripped a trench in the ground that emphasized the city’s racial division, and diverted automobile traffic from the East Side’s once-thriving business strips to a limited-access expressway that shuttles commuters from downtown Buffalo to the northern suburbs in about 10 minutes on a clear day.

In other words: Making the city a backyard to its suburbs. Depressing property values. Starving small businesses on Jefferson and Fillmore of customers and abetting the evisceration of those business districts. Subjecting two generations of residents surrounding the expressway to air and noise pollution.

As for relieving the ever-increasing congestion Gallancy worried about, the Kensington today carries about 70,000 vehicles per day. In other words, traffic volume between downtown and the northern and eastern suburbs is about the same as it was in 1958. The region’s population hasn’t grown to fill the capacity created by the state’s highway engineers. It hasn’t grown at all. This city incurred all the negative impacts of an urban expressway, and it turns out we didn’t even need it.

The loss of Humboldt Parkway in favor of an entrenched highway cutting the city in two ranks high on the list of most regretted and frequently bemoaned Buffalo planning mistakes, right alongside the failure to locate UB’s new campus downtown.

It is also the first of these mid-century blunders that the region has a real shot at reversing. The New York State Department of Transportation, armed with $2 million in federal funds, is currently shopping for a consultant to evaluate possible ways to restore Humboldt Parkway. “This is a chance to undo something that never should have happened,” says Stephanie Barber of Restoring Our Community Coalition, a group of neighborhood stakeholders who have been advocating for restoration of Humboldt Parkway and helping NYSDOT to define the goals of the project, from scope and design issues to health impacts and community benefit agreements.

The Kensington is in rough physical shape anyway, Barber says—witness ongoing emergency roadwork on sections of the expressway, as well as work on the retaining walls and railings between Jefferson and Michigan. NYSDOT is going to have to invest heavily in repairs soon, Barber says, so now is the time to push for a dramatic reclamation project of the sort that at least a dozen US cities have undertaken in recent years to rid themselves of urban expressways.

Presently, NYSDOT seems to favor two roughly defined design options, both of which entail capping the Kensington from Best Street to Delavan Avenue, and installing an approximation of Olmsted’s parkway on top of the cap.

Last August, Mayor Byron Brown introduced a new design option that has attracted considerable interest among local transit activists: burying the entire thing, from Oak Street to Delavan, and replacing the high-speed, limited-access expressway with a low-speed, at-grade boulevard, fully integrating the traffic it carries with the urban street grid. Coupled with the long-debated plan to slow down the Scajaquada Expressway and convert it to a walkable, bikable boulevard, Brown’s recommendation presents the city an opportunity to restore vital elements of the city’s Olmsted patronage, and to join the 21st century in regard to urban transit planning.

Cover it or bury it?

According to Craig Mozrall of NYSDOT, there are five design options under consideration. First, the do nothing option. Second, simply improve retaining walls and railings, plus landscaping, which is what is happening between Jefferson and Michigan now.

next two options involve capping the Kensington between Best Street and Delavan Avenue. The trench that carries the Kensington is not deep enough to be capped as is, so the first capping option envisions a surface median that is raised four feet above grade, with two lanes of traffic on each side of a landscaped parkway. The second capping option is slightly more dramatic: It entails digging the trench four feet deeper, resurfacing the expressway, then building the new parkway at grade over top.

Finally, there’s the fifth option introduced by Mayor Brown last summer: Fill in the expressway and replace it with an at-grade, tree-lined urban boulevard comprising eight lanes. In each direction there would be a slip road and three inner lanes, with parkway in between. In his August letter, Brown referred NYSDOT to the Central Freeway Replacement Project in San Francisco, in which an urban expressway was demolished and replaced with an expanded Octavia Boulevard, removing what many considered a blight on the city’s landscape and injecting the proximate business district with new vitality, while managing to accommodate the displaced traffic.

The burial option has at least two distinct advantages, according to advocates such as the New Millennium Group, which has written a brief in support of Brown’s recommendation. First, burying is considerably cheaper than capping. A rough cost estimate for the project in 2007 tagged the second capping option at $265 million for covering less than one mile of expressway. When people talk about the price now—and it’s a guessing game, to be sure, until the study gets underway—the figure ranges from $350 million to $500 million. No funding for construction of the project has yet been identified.

On the other hand, the cost of simply burying the expressway is probably less than $100 million.

The second advantage is that burying the expressway will return commuter traffic to surface roads, which means some of it will disperse and be absorbed into the urban street grid. Vehicle traffic that disappeared from business districts on Genesee, Walden, Fillmore, and Jefferson when the Kensington was opened will, hopefully, reappear, as motorists seek new routes between downtown and the suburbs.

NYSDOT’s response to Brown’s letter was tepid: Alan Taylor, regional design engineer, wrote that the department had not considered any option that involved “permanent impacts or changes to the operation of Route 33.”

“To add that alternative would change the classification of the study under NEPA,” Mozrall explains, referring to the National Environmental Protection Act, “from an environmental assessment to a full-blown environmental impact statement, because that would have a drastic effect on the through traffic that’s running on the expressway right now.”

An EIS can take substantially longer than an environmental assessment, which Mozrall says will probably take two to three years as it is. Still, he added, if the citizens advisory group, the mayor, the Common Council, or any of the other politicians driving this project told NYSDOT to get serious about that fifth option, then NYSDOT would do it.

But the mayor’s office has not communicated with NYSDOT since sending that letter last summer, and the mayor’s office did not respond to numerous requests from this newspaper for comment on the issue.

“We haven’t heard back from the city that that is in fact what they want to do,” Mozrall said. “We did tell the city that we would talk about that option in the scoping action…but as far as the purpose and need of the projects that have been identified by the advisory committee, the actual changing of the expressway into an eight-lane boulevard does not meet the purpose and need. We don’t see how that would reflect original Olmsted design, which only had two lanes of traffic separated by a wide parkway.”

Setting priorities

“They have the wrong objectives,” says John Norquist, former mayor of Milwaukee and president for the Congress for the New Urbanism. Norquist has displayed particular interest in Buffalo’s transit projects, weighing in on reconstructing Route 5, dismantling the Skyway, and expanding the Peace Bridge plaza. His gut reaction to NYSDOT, and to transportation departments generally, is distrust. DOTs everywhere, he explains, are principally concerned with relieving traffic congestion, and moving cars from one place to another as quickly as possible.

“Having through traffic not have to slow down through town should not be a priority for the City of Buffalo,” Norquist says. “It hasn’t done Buffalo any good to have that criterion. If the objective of the expressways was to eliminate congestion, they worked perfectly, because congestion is not a big problem in Buffalo—not just traffic congestion but money congestion, people congestion. Everything’s been decongested because of this narrow objective of fighting congestion.”

An expressway, he says, is a rural form that doesn’t belong in the city. Few European cities have expressways within their city boundaries. Vancouver, which has some of the highest property values in North America, has no expressways whatsoever within the city boundaries.

“But Buffalo’s leaders made a decision, with the help of Robert Moses and the state DOT, that Buffalo should be a great place to drive trucks through,” says Norquist. “So they dug up Olmsted’s boulevard, which added value to Buffalo, and put in this thing that doesn’t add value to Buffalo.”

Under Norquist, Milwaukee dismantled some of its mid-century highway system. A few years ago, Toronto tore down the eastern section of the Gardiner Expressway. Seoul, South Korea removed one of its busiest expressways, carrying 100,000 cars per day, spurring private investment in the real estate along the boulevard that replaced it. The Champs d’Elysees in Paris carries 80,000 cars per day. The New Millennium Group’s brief (available at www.nmgonline.org) refers to Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn, an urban boulevard with an Olmsted pedigree that carries 70,000 cars daily, just as the Kensington does. There is plenty of evidence to be found in other cities that urban boulevards offer more than adequate traffic capacity, while conferring economic, aesthetic, and health benefits to the surrounding community.

“In my mind, [burying the Kensington] should be considered for the additional opportunities it provides to the city as a whole,” says Justin Booth, chair of the City of Buffalo’s Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Board, which NYSDOT asked for input on the project. The Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Board promotes a “complete streets” approach to transportation planning, wherein road projects take into account the needs of pedestrians and bicyclists, in addition to the welfare of adjacent communities.

Booth is concerned about air pollution. Currently the car and truck exhaust disperses into the air. (That’s problematic enough, according to Stephanie Barber of Restoring Our Community Coalition, who cites widespread upper respiratory health issues in her community.) If the expressway is capped, the exhaust will need to be vented, which means concentrated exposure at its outlets. Where will that be? Booth wonders, too, if the caps NYSDOT envisions will support large shade trees. He’s also concerned that the high cost of the capping options means that the project will never move beyond the current $2 million study.

And, like Norquist, Booth believes the project goals should be set by the community, not by NYSDOT, and he suspects that the baseline goal of maintaining Route 33 as it exists begins with the state, not with the community. “Right now the Kensington functions, in my opinion, as an auto sewer,” he says. “It doesn’t diffuse the traffic into the community, it funnels people from point A to point B. The goal of the project is to maintain the current traffic capacity, which you could with the boulevard. But, to be honest, do we want to? It’s not benefiting the city of Buffalo, it’s benefiting the commuters who cut through the city of Buffalo to the detriment of the neighborhood that surrounds it.”

What happens next

The official position of Restoring Our Community Coalition, according to Barber, is to put every option on the table. Barber thinks the option advanced by Mayor Brown and supported by New Millennium Group ought to be given full consideration during the study phase of the project, as should all other design possibilities. “I think in a study you want to look at every single idea thoroughly,” she says. “Let the pluses and minuses be weighed fairly.”

It’s been a long haul getting to the point of a funded study. According to Barber, who lives in Hamlin Park, the notion of reclaiming Humboldt Parkway was first promoted by a resident named Clarke Eaton a dozen years ago. Eaton would make presentations, complete with drawings and brochures, to the local homeowners association. (“We’d allow him to come talk to us about once a quarter,” Barber says.) Pie in the sky, Barber recalls people thinking. “We all thought it was a good idea,” she says, “but we just thought there was no chance.”

Over the years, Eaton’s idea began to acquire advocates. He collected letters of support from politicians and community leaders. As health impacts from exposure to exhaust began to manifest in the community, Barber and other neighbors began to see some sort of remediation of the mistake that was the Kensington as a necessity. That coupled with the clear economic injustice imposed by the construction of the Kensington Expressway galvanized the community into action.

“If you look at the expressway, which used to be a parkway, and look at what’s happening a block from there, the whole community is deteriorating,” Barber says. “We started looking at Bidwell Parkway and Colonial Drive, and we looked at a block from there, and those neighborhoods are thriving.”

They applied pressure to State Senator Antoine Thompson and Assemblywoman Crystal Peoples-Stokes to put their weight behind the issue in Albany. They recruited Masten District Councilman Demone Smith as an advocate. They reached out to NYSDOT. Now there exists the possibility that this colossal mistake can be buried—under a cap or under rock and soil—forever. During the two or three years the study will take to complete, elected officials must work on finding funding for construction.

“If we can fix something like this, we can fix a lot of things,” Barber says. “I don’t want my great-grandchildren to say, ‘Whose idea was this?’”

Images on this page and the cover photo on this week’s print Artvoice were provided courtesy of David Torke. Visit his blog fix buffalo today.”

“A Buffalo Neighborhood Renews Its Olmsted Legacy (2012)”

Below article appeared in Library of American Landscape History.

“A Buffalo Neighborhood Renews Its Olmsted Legacy (2012)

Humboldt Park, Buffalo, New York

When Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux began work on the nation’s first comprehensive municipal park system in 1869, Buffalo was the eighth largest city in the country and one of the busiest ports on earth. Functioning as the gateway to the Midwest via the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes, the city offered the partners an opportunity to improve an existing grid with a green network of parks and sinuous parkways. Late in life, Olmsted declared Buffalo to be “the best planned city, as to its streets, public places, and grounds, in the United States, if not the world.””

“The appeal of a lushly planted public landscape attracted upscale development, and soon the works of leading architects from New York City and Chicago were enlivening the city’s streets. Into the mid-twentieth century, the parks’ mature plantings provided Buffalo’s neighborhoods with high-canopied shade, lakes and picnic groves, and miles of walking paths. Two-hundred-foot-wide median strips in the parkways even boasted equestrian trails in a woodland setting, while cars whooshed past on either side.

Olmsted and Vaux, however, did not foresee the trends that cast Buffalo among the financially distressed cities of the “rust belt” in the late twentieth century. Like parks in other large northeastern cities, Buffalo’s were neglected and, in some cases, destroyed. The Olmsted legacy faded from popular memory. “When I first moved to Buffalo five years ago, most citizens here didn’t even recognize the Olmsted name. That has changed dramatically,” says Thomas Herrera-Mishler, president and chief executive officer of Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy. Now the regional convention and visitors bureau, Visit Buffalo Niagara, touts the Olmsted parks among Buffalo’s attractions. “This is the green infrastructure that gives us a competitive edge,” Herrera-Mishler says. The 2011 National Trust for Historic Preservation conference, hosted in Buffalo in October of last year, brought the Olmsted legacy to national attention, featuring park tours by members of the National Association for Olmsted Parks, the Trust for Public Land, and other nationally prominent historic preservation advocates.

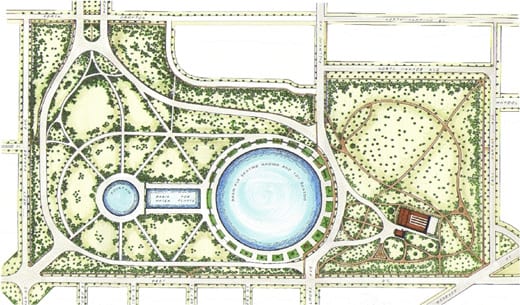

Equally important, the conference helped raise local awareness of the park system’s cachet. “The conference brought the valued perspective of experts who recognize these treasures, giving residents a greater appreciation for them,” says Otis Glover, strategic planner and external affairs officer at the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy. “All of our cultural treasures are in the footprint of the Olmsted landscape.” In particular, the attention boosted long-standing efforts by residents to revitalize a predominantly African American neighborhood surrounding one of the city’s principal Olmsted parks, on Buffalo’s east side. Olmsted designed the park, originally known as the Parade, as a military parade ground. It was used for this purpose only once, and in 1896, John Charles Olmsted redesigned it for general recreation, adding three axial water features, including a vast circular pool for wading, toy boating, and skating. Humboldt Basin, at five hundred feet in diameter and five acres in area, remains the country’s largest wading pool. Its grandeur was echoed in other amenities—including greenhouses and a casino building—throughout the park. After its redesign, the park was renamed Humboldt Park, after Humboldt Parkway, itself named after the great explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. Like the system’s other parkways, this was a broad median of wooded trails and grassy meadows, which created a pedestrian and vehicular link to Delaware Park, the system’s anchor.

Various encroachments gobbled up space in Humboldt Park during the twentieth century. The crowning blow, however, came in the 1960s with the construction of Kensington Expressway, a multilane highway that lopped off the park’s northwest corner and erased the parkway, splitting the neighborhood and severing it from the rest of the city. “For four decades the community has been devastated by disenfranchisement and division,” Glover says. For him and others, the multigenerational impact of the highway underscores the profound significance of access to open space and citywide connections. The sunken six-lane expressway, locally dubbed “the canyon,” whisks suburban commuters to downtown offices, stranding local businesses and creating an aesthetic blight that has contributed to sinking property values. Humboldt Park was renamed to honor Martin Luther King Jr. in 1977, but it continued to decay. The water features, including the basin, stood empty. A plan to take parkland and build a magnet school next to the Buffalo Museum of Science, which had already been built in the park, galvanized the Buffalo Friends of the Olmsted Parks, sparking a battle that ended in the state supreme court. The battle was lost, but the organization that eventually grew into the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy was born.

In the mid-1990s, the community and the conservancy started actively campaigning to revitalize the neighborhood and its park, led by the Martin Luther King Jr. Coalition. When the city announced plans to convert the abandoned Humboldt Basin into a fishing pond, the neighborhood mounted a protest and demanded the return of the wading pool. Richard Cummings, a businessman who lives on the park, is a trustee of both the coalition and the parks conservancy. “We want to reclaim the community as it was in the early 1960s, before the destruction of the Humboldt Parkway,” he says. Cummings attests that the green landscape of the former park and parkway—and the loss of it—exerts a tangible influence: “It affects pride and real-estate value and the way people approach our community.”

During the same period, the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy had taken over maintenance of the Buffalo Olmsted parks and embarked on a comprehensive master planning process, soliciting the community’s views about how to rehabilitate Martin Luther King Jr. Park. Together they selected a number of major projects, including the wading pool. Bringing back the pool proved complicated, however; modern health and safety codes required fencing, a massive water-purification system, and sixty-five lifeguards for a pool less than three feet deep. “So we focused on how to make water available in some form for seasonal recreation,” says landscape architect Mark V. Mistretta, RLA, ASLA, of Wendel Companies, a Buffalo native and a founding member of the parks conservancy. “We decided to create a large splash pad, providing big spray events in summer. In spring and fall it will be a reflective basin. When it freezes, we will have a great skating rink.” With $4.2 million in funding from the City of Buffalo, the State of New York, and BlueCross BlueShield of Western New York, the pool will open this summer.

In a parallel effort, the Reclaiming Our Community Coalition, which includes the parks conservancy as well as businesses and institutions, such as the Buffalo Museum of Science, that are located in and around the park, is advocating for the city to cap more than a mile of the Kensington Expressway and replicate the former parkway landscape on the covered portion, says Cummings, who also serves on this coalition’s board. The state has provided $2 million to fund preliminary studies for the proposed project, which would cost an estimated $465 million, according to a recent Buffalo newspaper report. LALH vice president Ethan Carr, FASLA, a trustee of the National Association for Olmsted Parks, has been speaking with coalition members. Carr agrees that “restoring the parkway is about restoring the neighborhood.” He adds, “Olmsted’s vision was never about just providing trees and grass. It wasn’t just about building parks and parkways. It was about building communities, creating vital neighborhoods that were centered around the parks. That’s why they were built.”

—Jane Roy Brown”

To download a .pdf of this article, click here.

“Now is the Time to Demand the Downgrading of Buffalo’s Expressways”

Below article/image was featured in Buffalo Rising, and posted by Mike Puma, August 2, 2013.

“Now is the Time to Demand the Downgrading of Buffalo’s Expressways

This post (everything after this paragraph) was written by Bradley Bethel Jr. who is active in many east side organizations and movements including the Restoring Our Community Coalition, which is working with the NYSDOT for capping a portion of the Kensington Expressway and restoring a part of Olmsted’s vision for the east side with Humboldt Parkway.”

“The entry image in the post was taken this morning at 8:30 from the pedestrian bridge where Lincoln Parkway was severed into two separate streets by the expressway. I stood there for at least 15 minutes and the volume of traffic you see in this image was consistently next to nothing. As Steel aptly pointed out in his recent article, rush hour, our city grid is capable of absorbing this traffic with only a few extra minutes tacked on for suburban commuters. It’s time to rethink our expressway system beginning with the Scajaquada and moving on to the Kensington. Downgrading or completely removing these eyesores that tear communities apart is a once in a generation opportunity. Imagine filling the Kensington Expressway, restoring Humboldt Parkway, and utilizing the below grade portion for a new light rail line from downtown directly to the airport, it’s a conversation worth having. Our last generation left us with a monster that divided neighborhoods, destroyed Buffalo’s grandest parkway, and has caused serious health concerns in adjacent neighborhoods. It’s the responsibility of this generation of Buffalonians to stand up and fight for this so that we can leave a better legacy for our city for future generations to enjoy. Now I’ll leave you to enjoy Brad’s post!

There is an ongoing rivalry between urban planning and suburban planning for Buffalo’s future. Urban planning favors sustainable, accessible neighborhoods that can accommodate both pedestrians and motorists. Suburban planning, known as “sprawl”, favors vast communities where the automobile comes first. These approaches have dueled on many current efforts to improve transportation in and around the city.

One example is the downgrade proposal for the Scajaquada Expressway Route 198 (NYSDOT Project No. 5470.22). The Scajaquada Expressway was implemented in anticipation for motor increase, ironically during a time of mass decline in the region’s population. In relation to Delaware Park, daily noise pollution and limited accessibility have both been unwelcome frustrations to an historic setting meant for tranquility. As we have seen with such sprawl-based planning, it has compromised Buffalo’s heritage in such a way that still has yet to be remedied.

Among four downgrading alternatives up for public discussion, one includes reducing Scajaquada’s speed limit from 50 mph to 40 mph. It is the only alternative that has been pressed by the New York State Department of Transportation for a small number of stakeholders. A somewhat apathetic solution to the intrusion of the existing Route 198, it does symbolize the DOT’s own attitude towards the city and its residents.

I am not against the automobile. I am a driver myself out of necessity, and as you can tell, none of the Scajaquada proposals are going to banish cars completely from Delaware Park. However, there is a growing awareness of the damaging effects that sprawl-based planning has had on local economics.

The motorist spends, on annual renewals in car inspection, registration, and insurance, as well as annual repairs and maintenance an untold average of thousands each year. Buffalo’s gas prices are consistently above the national average, and as of this writing, prices are once again inching towards the $4.00 mark. As downtown development progresses, and with a tough economy in mind, residents of newly-built apartments are discovering the benefits of a long-ignored alternative. In the roughly third of Buffalo residents living without a car, a growing portion are doing so by choice.

In some ways, Buffalo has already begun to embrace the call for multi-modal transportation. The city is moving forward with a plan to make more “complete” streets; streets where motorists, pedestrians, and bicyclers can travel in harmony. Streetscaping on main thoroughfares have included lanes and labels reserved for bicycle traffic. Continued developments in the Medical Campus and the waterfront, as well as increased bus and rail ridership have prompted the NFTA to reopen discussions about expanding the Metro rail.

Imagine another Scajaquada Downgrade alternative. Scajaquada would no longer be an expressway, because traffic would be reduced to 30 mph. But motorists can still travel to key areas of the city on a boulevard that pays respect to its Olmstedian surroundings. It would also open the door for more pedestrian safety and accessibility throughout the park.

The DOT however, appears reluctant to acknowledge the calls for change, evidenced by how the Scajaquada Downgrade has been on and off the shelf for the past 20 years. Their negligence is leaving the general public in the dark on a 2014 deadline before a proposal is finalized. Moreover, it puts Buffalo at risk of once again falling behind the rest of the nation, at the very time when the city is finally proving to be capable of grand accomplishments.”

To download a .pdf of this article, click here.

“Restoring Humboldt Parkway

Community Meeting July 22nd”

This article appeared in WNYmedia.com July 18, 2014.

“Restoring Humbolt Parkway Community Meeting July 22nd

Because of the persistence of neighbors and institutions around Humboldt Parkway, the dream of a “Green Parkway” to restore the community is coming into clearer vision. A new University at Buffalo report has been released, which documents the economic impact of a restored Humboldt Parkway. In a study commissioned by the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT), the UB School of Architecture and Planning in conjunction with its Regional Institute Urban Design Project, a team of experts led by principal investigator, Robert Shibley, has ascertained that such a project would have a minimal regional economic impact exceeding $1 Billion and construction employment of hundreds of jobs. In the best case scenario, the impact would catalyze the complete revitalization of an area from the Fillmore Business District to the Jefferson Street Business District and the residential neighborhoods in between. Such revitalization would spur new mixed-use development, improving property values and household wealth.”

“The Restore Our Community Coalition (ROCC) will share highlights of the UB report with the general public on Tuesday, July 22, 2014 from 6:00 – 8:00 PM at the Buffalo Museum of Science Cummings Room. Key study investigators Paul Ray of the UB Urban Design Project and Professor Hiro Hata, who led a team to develop potential implementation designs for a green parkway, will also be on hand. The target audience is residents of Hamlin Park, known as the Hamlin Park Taxpayers Association, and block club advocates from Humboldt Parkway, East Ferry, and Delevan Streets, as well as owners of neighborhood businesses from Fillmore to Jefferson. The meeting is open to the public, and the media is invited as well.

ROCC chairperson Stephanie Geter stated, “We want to update the community on the progress toward reaching our goal to restore the Olmsted vision of a vibrant, green community space, to remediate the devastation caused by the construction of Route 33, and to create a beautiful gateway to Buffalo’s Medical Corridor. ROCC came together in 2007 to bring this issue to the attention of local and state leaders, focusing our coalition power on the New York State Department of Transportation. Much work has been going on behind the scenes, and we have a plan to make this vision a reality.”

Indeed, the vision is not a new one. In the 1870’s, Frederick Law Olmsted articulated a vision of a “city within a park” that became the nation’s first interconnected park system. A major corridor in the system was Humboldt Parkway connecting Delaware Park with the former “Parade,” later renamed Humboldt Park, and now called Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Park. Olmsted Parks Conservancy President Thomas Herrera-Mishler notes that Humboldt Parkway was designed to allow users to travel from one park to another without leaving the serenity of the park-like atmosphere. He says, “six rows of mature shade trees once provided a wonderful canopy not only to connect Olmsted’s Delaware and Parade Parks, but also to provide a valuable green space where everyone was welcome to enjoy nature, enhancing the visual character and quality of life for the whole community. Restoring this green anchor on the East Side of Buffalo is a major priority of the Conservancy.”

Richard Cummings, President of the Black Chamber of Commerce, asserts that “while the Kensington Expressway construction led to community devastation, we are optimistic that some of the damage can be reversed. Even though the introduction of the expressway in the 60’s isolated the East Side from the rest of Buffalo, we are working with businesses, residents and city leaders to reverse that decline. We believe that our community can be restored.”

The Humboldt community includes neighbors, business owners, cultural institutions and tourist attractions. “We absolutely embrace the vision to re-create a viable, walkable, green environment on all sides of the Museum”, says Mark Mortenson of the Buffalo Museum of Science. “That is the environment that the Museum celebrated until it was tragically lost by the construction of the Kensington Expressway.”

The idea to cover a portion of Route 33 may have seemed farfetched to many local residents and even elected officials and transportation leaders, but the reality is that there is a movement across America to remove urban freeway systems in order to create more livable cities. “Highways to Boulevards” is a major initiative of the Congress for New Urbanism (CNU), which came to Buffalo for its 22nd Annual Congress this past June. The 4 day conference was themed “The Resilient Community,” and several sessions addressed issues related to the restoration of the Humboldt Parkway community. One of the workshops was dedicated to strategies for achieving freeway removal, another discussed the “Olmsted vs. Moses” theories juxtaposing urban planning from a sustainable parks and parkways perspective versus a highway construction agenda such as the one that led to the New York State Robert Moses Highway System. The CNU charter states that it stands “for the restoration of existing urban centers… the conservation of natural environments and the preservation of our built legacy.” Further they embrace principles and advocate for “restructuring of public policy and development practices… (to create) diverse neighborhoods designed for the pedestrian and transit as well as the car, and … urban places framed by architecture and landscape design that celebrate local history, climate, ecology and building practice.”

Conference attendee Karen Stanley Fleming, who serves as the Executive Director for ROCC, stated, “ I was elated to meet several leading planners and urbanism experts who affirmed the human, economic and environmental benefits of sustainable planning projects such as our proposal to create a green deck over a portion of Route 33. Projects like this are going on around the country, and at even greater expense that the projected $560 million that a Green Humboldt Deck would cost, because the point is that this in an investment, which will reap returns. It is not just a transportation cost to correct an urban sprawl mistake. An investment to turn part of this highway into a green boulevard will reap dividends in terms of job creation and increased property values. An investment to restore a Green Humboldt Parkway will bring to our Buffalo Renaissance the beautiful gateway that our Downtown Revitalization deserves.”

The public is invited to hear the progress and join the movement on

Tuesday, July 22, 2014

6:00 PM – 8:00 PM

Buffalo Museum of Science”